DSUTMA (Does Science Use Too Many Abbreviations)?

Science has a reputation for being very complicated, sometimes to its own detriment. One way that this manifests is the use of acronyms, initialisms, and other abbreviations, theoretically designed to make life easier for the reader but often, in my experience, leading to some confusion when read out of context.

To test this theory, I conducted the extremely scientific experiment of going to the open-access journal BMJ Open, and clicking on an article on the front page from the “Most Read Article” list (the category in this case was “Pharmacology and Therapeutics”). I then scrolled to the discussion section, where the first sentence reads as follows:

As you can see, there are indeed a large number of abbreviations in this example. But how prevalent is this, and is it a problem?

How often do papers use abbreviations?

A paper published in 2020 sought to see how widely used acronyms were in scientific papers. Researchers analyzed around 24 million articles, published from the 1950s to the 2010s. They found over 1 million unique acronyms had been used, but of those, only 0.2% (just over 2000) were used regularly, and about 4 in 5 acronyms were used less than 10 times ever. Around 20% of titles included an acronym, and around 75% of abstracts. They also found that the prevalence increased over time, from 0.7 per 100 words in 1950 to 2.4 per 100 by 2019.

What’s clear, then, is that acronyms are not only very prevalent within science publications, they are increasingly prevalent. It is also clear that the vast majority of acronyms are acronyms that are hardly ever used.

The researchers also compiled a list of the most commonly used acronyms:

Looking at this list, we can see that DNA is (by far) the most used acronym, which makes sense, and is one that’s hard to complain about as its more or less universally understood. Others, like CD4 (Cluster of differentiation antigen 4) are ones that laypeople such as myself have never heard of, but I assume are relatively well-known within their fields. 6 of the 20, however, appear to be acronyms that can mean multiple things, including things that could definitely be in the same paper (e.g. United States/Ultrasound/Urinary system).

So is this a problem?

There have been calls from several people about reducing the use of abbreviations iin science, including a suggestion to reduce the use to three acronyms, and a recommendation by the American Chemical Society to avoid abbreviations in the titles of papers (ironically, they wrote this in the “ACS Style Guide”).

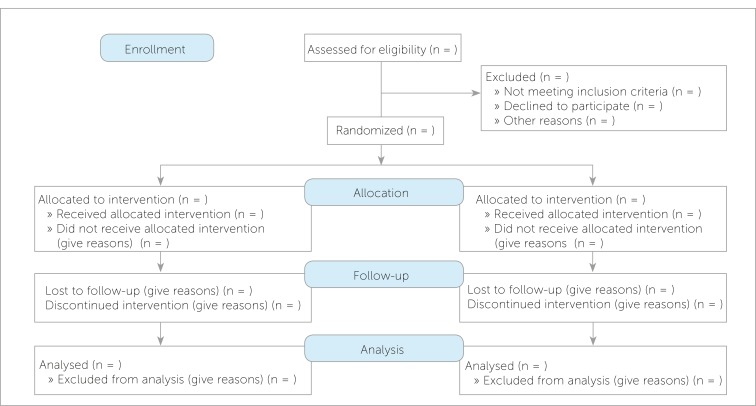

In defence of abbreviations, there are many good reasons why scientists use them. One is that in many cases, the names of things are long and/or complicated, and using acronyms can help cut down on that, allow writing to flow easier and (particularly in the case of things like grants) reduce the length of writing. Another is that in many fields, abbreviations are part of the common language of researchers, and therefore are both widely-used among peers and also widely-understood. Considering the fact that the audience of scientific publications is usually other scientists, it makes sense to use language common with this audience. When you read a paper, they will always explain what an abbreviation means the first time they use it, to avoid confusion. Acronyms are also sometimes used by researchers (and politicians) to coin a catchy name for something, like the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram, which otherwise might be more forgettable.

On the other hand, there are many issues with the use of abbreviations. The obvious one is that many times, it just isn’t that clear what they mean. It’s common to skim a paper rather than read it fully, and so that can become a lot more difficult when abbreviations are used throughout the paper. Even when you’re reading a paper fully, it’s not unusual to reach a table that contains 10 different abbreviations, none of which are obvious, and then have to flip back and check what each one means. Sometimes authors assume an abbreviation is well-known, so they don’t clarify what it means, which can lead to additional confusion. A study found that a full 22% of abstracts used language so complicated that they cannot be considered readable by someone with college-level English.

The use of abbreviations as jargon can also harm interdisciplinarity. By relying on language and ways of communicating developed in specific fields, abbreviations can make it seem more daunting for people from different disciplines to understand papers. While a researcher can of course check to see what the acronyms and initialisms all mean, it is inevitable that they will feel alienated when they see abbreviations that they don’t recognize being used again and again. One study found, unsurprisingly, that using more jargon in your title and abstract significantly reduces the chances of being cited.

There are also certain abbreviations that need to be considered more in-depth before they are used. Consider the examples mentioned above of acronyms that mean different things in different contexts. Another example is the use of AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander), which has been noted in the past by groups such as the Asian American Journalists Association as one that can be controversial, as it groups together communities that sometimes might want to be differentiated. Researchers might default to using acronyms like these without really thinking about what the implications of using them might be.

So what to do?

Overall, there are bigger issues with science communication than the use of abbreviations. But abbreviations are definitely part of a larger trend of insularity within science publications that reduces the amount that articles can be understood and limits the impact they can make outside the scientific community. For all of their benefits, the current state of abbreviations in science leaves a lot to be desired, and is probably doing more harm than good. While abbreviations still have their place, there should be more consideration by authors of the ways in which they are using them. Abbreviations that are understood by many, and acronyms that are used to aid memorability, are examples of abbreviations that can be very helpful. Other abbreviations, like ones that will never be used again, ones that can be confused with other abbreviations, or ones that can alienate or dehumanize groups, should be avoided if possible. While it is obviously a subjective process, researchers taking more time to consider when and how to use abbreviations will lead to greater interdisciplinarity, comprehensibility, and impact for their work.

Sources

Main source:

Other:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2020.2581